Arkady Ostrovsky, the author of The Invention of Russia, was a drama student who went to England to study English literature and then became a journalist, so his pedigree may be among the most unlikable on the planet. He was a Soviet citizen, however, and is a Russian, and the liberal perspective on Russia is useful in understanding why those liberals are so deranged today.

The book is focused on Soviet control over print and Russian control over television. As the prologue says: “things that did not exist could be turned into reality by harnessing the power of television.” The book was written in 2015, but by 2023, the idea that there is something unique to Russia in this mode of propaganda is obviously wrong. As Scott Adams said during the 2016 Trump campaign, the left and right are seeing two movies on the same screen. When you’re in the movie, it’s much harder to see when your side is doing the same thing as the other.

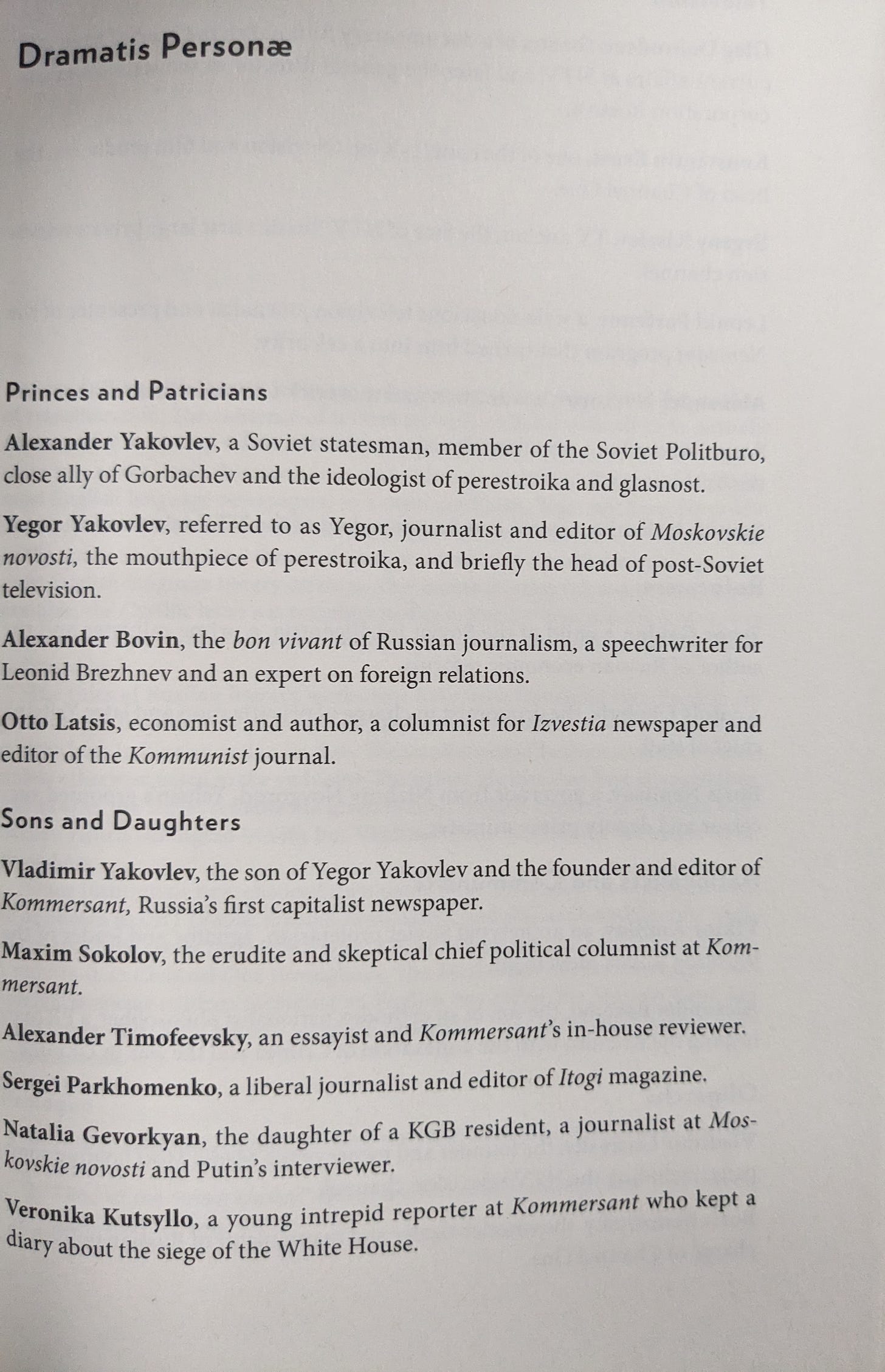

Before the review, it might be useful to keep these two pages for reference, as I won’t be fully explaining every single character in the story.

The author begins his story with the life of Yegor Yakovlev, the head of Soviet Television by the last day of the Soviet Union, but before that, during the Krushchev and Brezhnev years, he was a journalist and reformer. The author focuses heavily on the written and spoken word, literally titling the first part of the book “In The Beginning Was The Word.” After Stalin’s death and the slow un-tightening of the Soviet Union, the published word had an instrumental role in the rehabilitation of Russia after Stalin’s purges. By the time of Gorbachev, publications such as Novy Mir were publishing The Gulag Archipelago in the Soviet Union for the first time.

Alexander Yakovlev, the other Yakovlev the book focuses on, although unrelated to each other, was put in charge of Soviet ideology by Gorbachev. He was previously “exiled” to Canada as an ambassador by Brezhnev after fighting a battle with nationalists and Stalinists in over the direction of Soviet ideology. Yakovlev opposed nationalism and anti-Semitism “with every fiber of his soul” and was fighting against what he saw as nascent fascism in Russia. As Gorbachev’s man, he wrote privately that Soviet ideology needed the “neo-religion” of Marxism removed, replaced by a free market and private ownership.

Alexander Yakovlev offered the editorship of Ogonyok, one of two publications selected for promoting perestroika, to Vitaly Korotich a poet from Kiev who spoke out against the censorship of the Chernobyl incident. At the same time, Yegor Yakovlev was offered the editorship of the other selected publication, Moskovskie novosti (Moscow news).

The book rather frustratingly takes its time getting to the core material—on page 99 the concept of Russian sovereignty is finally introduced:

“In May 1990 Yeltsin was elected president of Russia—the largest and most important of the Soviet republics—and a month later, on June 12, 1990, Russia’s Supreme Soviet followed the example of Lithuania and voted for Russia’s sovereignty, even though nobody knew what this really meant. The idea of Russian sovereignty seemed absurd. As Chudakova noted in her diary at the time, “Who is Russia seeking sovereignty from, the polar bears?” But then she added. “Perhaps this is an ugly and strange way of overcoming several decades of non-historic life.” For Yeltsin, however, Russian sovereignty meant something less metaphysical. It meant that Russia’s government, with him as its legitimate head, was taking possession of all natural resources and industrial assets on its territory.”

As the KGB coup was underway in Moscow, both Yakovlevs played their own parts in the events in Moscow. As Yeltsin was taking command of the military, Yegor Yakovlev put himself in charge of the liberal media, bringing the editors of the newspapers closed by the government into his office and publishing one common newspaper together, Obshchaya gazeta, using the presses of the first private newspaper, Kommersant, which was edited by his son, Vladimir.

Alexander Yakovlev, after the coup, spoke to the crowd angrily ready to sack the KGB headquarters, and led them away to Manezh Square.

The book really gets interesting when it reaches chapter four and starts talking about the next generation. The young adults of Russia did not believe in socialism like their liberal but more conservative fathers. For the last issue of Moskovskie novosti in 1991, Yegor Yakovlev interviewed his own son. Vladimir was an entrepreneur, the founder of the paper Kommersant, and believed in the Russian business man as the new social force shaping the country. Yegor Yakovlev could not understand his son’s capitalist intentions.

Vladimir Yakovlev trafficked in facts, something formerly only a privilege of the powerful, even after the opening of state media. As a member of that class, Vladimir had access to telephone numbers and other information that the public did not. He created a cooperative called Fakt that would provide such information for a ruble. He wanted to create the Russian New York Times, and he created his own news agency, Postfaktum, so supply the information. His new business partner Gleb Pavlovsky, a former dissident from Odessa was put in charge of it, with Vladimir becoming the founding editor of the paper, Kommersant.

The paper was founded at a time when the country was not yet entirely open. The father edited Moskovskie novosti, which in its own time was revolutionary but still tied to Soviet ideology. (p. 65):

“Moskovskie novosti did not adhere to Western notions of a newspaper. Fact-based material was still forbidden. The news was not gathered by the newspaper but was distributed through the Soviet telegraphic agency TASS. For example, one of the biggest news items of the first perestroika years, the release of Andrei Sakharov from exile, which was splashed across front page of the the international press, was given forty words in Moskovskie novosti at the bottom of page three—a space usually reserved for corrections.”

The fact that the newspaper contained any information at all that would previously only result in secrecy resulted in a joke about the paper:

(p. 66):

“What was published was not new—it had long been the subject of private discussions around kitchen tables. What was “new” was the fact that this could now be printed in a newspaper under someone’s byline, that things that had been banished into the world of samizdat were now published. The very existence of such a paper was the biggest news of all.

A joke started circulating in Moscow:

One friend telephones another:

“Have you read the latest issue of Moskovskie novosti?”

“No, what’s in there?”

“It is not something we can talk about on the phone.””

The son’s paper was the opposite of the fathers (p.125):

“Kommersant was the antithesis of Moskovskie novosti and a reaction to it. It rejected civic pathos, its elevated language, its speaking of the Truth, capitalized and accentuated with exclamation marks, its sense of calling and duty, its political stand. “What we did was antijournalism, from the point of view of my father’s circle. Theirs was journalism of opinion. Ours was journalism of facts,” Vladimir told me. Only a few of Kommersant’s reporters were Soviet-trained journalists. Most were intelligent young men and women who had never written a newspaper article in their life.”

The paper’s name was taken from the prerevolutionary paper Kommersant, an unremarkable trade sheet. The name, however, was a political message:

“But the fact that a newspaper with that title had existed in the past was more important than what kind of paper it really was at the time. Vladimir Yakovlev was not reviving an old newspaper, he was reinventing the past—supplying Russian capitalism with the biography it lacked.

The masthead of the newspaper carried an important message: “The newspaper was established in 1909. It did not come out from 1917 until 1990 for reasons outside editorial control.” Kommersant was defining a period, 1917-1990, and simply extracting it from its own experience. The entire Soviet era was being disposed of as irrelevant. If Kommersant had not come out in those years, why should they be of any interest?

“we did not know the history of the country well,” said Vladimir Yakovlev. “we saw the whole of the Soviet period as one muddy stretch, and we wanted to reconnect, to establish a connection with an era of common sense and normality.”

Kommersant fought against Soviet ideology, but its own rejection of Soviet culture—dissident or official—was deeply ideological. Anything that was touched by the Soviet aesthetics was out, regardless of its content or artistic merit. The “sons” were not only disposing of wooden Soviet language, newspaper headlines and party-minded literature; they were throwing out an entire layer of culture that contained, among other things, strong antidotes to nationalism and totalitarianism. By doing so, they severely damaged the country’s immunity to these viruses, making it easier, a decade later, to restore the symbols of Soviet imperial statehood.”

At this point, I imagine that the author is alluding to the rise of Putin and he adoption of Russian nationalism and probably some form of “totalitarianism,” from the author’s view. We should note here the importance of the idea that the entire Soviet period was not Russian history, but a giant, gaping hole in that history.

(p. 128):

“Kommersant readers and authors treated the Soviet civilization not as an object of study or reflection but as a playing ground for postmodernist games, a source of puns and caricatures. The written Soviet language, which had long lost its connection with literature, had become so petrified that it easily lent itself to this exercise. Post-Communist Russia lacked its own serious language to describe the biggest transformation of the century. Words such as truth, duty and heroism had been completely devalued. In 1990, the year when Kommersant started to publish, the literary historian Marietta Chudakova noted in her diary: “Do our people expect any ‘new word’ from themselves? No. Nobody expects anything. What could come out from such a total absence of pathos?”

The lack of words from the denigration of language is an interesting and similar problem that we face, as “truth” in our world is more similar to Soviet pravda, “duty” is nonexistent or at best something to be mocked, and “heroism” is inverted to describe often fictional accounts of the unsung heroism of black women scientists.

(p. 130):

“Lacking a new project or even a vision of the future, Russia searched for a mythical past. Those who came to power after the Soviet collapse, both in the Kremlin and in the media, portrayed themselves not as revolutionaries but as keepers or followers of traditions that had preceded the Soviet era. (The inauguration of Yeltsin as Russia’s first-ever president was said, absurdly, to have followed a long historic tradition.)

Alexander Timofeevsky, a young bellettrist who articulated the ideas of the thirty-something generation, enthused about Kommersant’s conservatism, its deliberate and measured voice, its sense of solidity, which “like in a thick, British paper implies a centuries-long stability of life, which has been set and planned for centuries.” Articles with enigmatic foreign words such as leasing and banking clearing and exchanges, he wrote, provided the illusion of a long and verdant tradition.

The fact that this new life was a pure invention did not bother him. “The common reproach that Kommersant lies a lot is irrelevant,” he wrote. “It does not matter. What maters is that it lies confidently and beautifully.””

Here we might be reminded of Donald Trump, who “lies confidently and beautifully” but who’s vision lacks substance. We might make a pun on the previous quotation:

“Lacking a new project or even a vision of the future, America searched for a mythical past. Those who came to power after the Bioleninist collapse, both in Washington and in the media, portrayed themselves not as revolutionaries but as keepers or followers of traditions that had preceded the Bioleninist era.”

(p. 131):

“In the early 1990s Russian capitalists bubbled up from underground. It started with black-marketeers, opportunists, adventurists, hustlers, and con men. Most had cut their teeth in cooperatives. Colorful characters, they marked themselves by dressing extravagantly and mostly tastelessly. They favored purple and fluorescent yellow jackets. But this bright facade did not mean that they were harmless. Poisonous flowers and plants often mark themselves out in bright colors—a form of defense or a warning to birds and animals: eat me, and you will die.

These bright bubbles were Kommersant’s people, those whom it wished to fashion and educate, but above all to whom it wished to give a veneer of respectability and self-awareness—or, to use Lenin’s term, “class consciousness.” “The most important quality in a newspaper is not its information or emotions but a sense of social belonging. You pick up a newspaper, and you feel part of a certain class,” Vladimir Yakovlev explained.”

Wow. Could he have describe the affect of something like the New York Times (which Yakovlev wished his paper to be) any more accurately? This is the real, powerful affect merely being a subscriber to a publication like this brings. The affect is felt even among those of us who watch YouTube or Odysee, Bitchute, and Rumble videos. We have a “class consciousness” of our own, in opposition to that created by the New York Times and similar publications.

(p. 134):

“The new class of businessmen that emerged from the rubble of the Soviet economy thought of themselves as the champions of capitalism as they understood it. In some ways they were victims of Soviet propaganda that portrayed capitalism as a cutthroat, cynical system where craftiness and ruthlessness were more important than integrity, where everyone screws each other and money is the only arbiter of success.

Russian capitalism was far removed from the concept of honest competition and fair play or Weber’s Protestant ethics. It was not built on a centuries-long tradition of private property, feudal honor and dignity. In fact, it hardly had any foundation at all, other than the Marxist-Leninist conception of private property as theft. Since Russia’s new businessmen favored property, they did not mind theft. The words conscience, morality and integrity were tainted by ideology and belonged to a different language—one that was used by their fathers’ generation. “For us these were swear-words which the Soviet system professed in its slogans while killing and depriving people,” Vladimir Yakovlev said.”

It’s clear how the Russian economic chaos after the end of the Soviet Union was inevitable if it adopted capitalism without Christian ethics. Liberalism can only function well among a religious people with a strong belief in their own moral creed; the people of Russia were not prepared for this.

The author comments on the importance of television in the Soviet Union. Television would be at the center of multiple coup attempts in Russia: (p. 146):

“The nationalists consolidated not around television but around old literary magazines such as Nash sovremennik and Den´. Television was in the hands of the liberals. Almost immediately after the August 1991 coup, Gorbachev had appointed Yegor Yakovlev to the top job (with Yeltsin’s approval). His first step was to clear the television center of the KGB staff who worked both openly and undercover. His second step was to dispose of Vremya—the main nine o’clock evening news program—and replace it with the plain-sounding Novosti (News). The change of title, theme tune and format was as symbolic as the lowering of the red flag over the Kremlin or the change of the Soviet anthem.

Vremya had a sacred status in the Soviet Union. Its two serious-looking, buttoned-ip presenter were the oracles of the Kremlin. It did not actually report the news but told the country what the Kremlin wanted its audience to think the news was. It was a nightly ritual in which nothing “new” or unpredictable could ever happen. Vremya, a name that in Russian means “time,” was as regular as the chimes of the Kremlin clock that preceded the program. Like time, Vremya seemed infinite. By changing the format, Yegor was removing the sacred function of television and desacralizing the state itself.”

After the June 1992 siege of the television center in Ostankino north of Moscow by hardcore Communists led by Viktor Anpilov, Yeltsin replaced Yegor with a more pliable man who would provide the Kremlin with whatever programming it desired. Both men understood the importance of television. After the siege, Yegor said “I don’t know why Anpilov and his people have not taken over the television center yet. I can’t imagine a more impotent executive power.” Yelstin said “I realized that ‘Ostankino’ is almost like a nuclear button. . . and that in charge of this button should not be a reflective intellectual but a different kind of person.”

In October 1993, another anti-Yelstin crowd led by Anpilov gathered and attacked the Ostankino television station and took it over. This was part of the events of the 1993 crisis in which the Russian parliament was taken over and by rebels.

After the new Russian constitution adopted in December 1993 put supreme powers in the hands of the President, “The media did not try to educate or engage the majority of the country in politics. Despite being owned by the state, they performed no public duty.”

Igor Malashenko founded the television network NTV. It’s target audience was the urban professional class. Unlike Soviet television, which attempted to pacify the audience, this new Russian television station sought to mobilize a class, like the print publication Kommersant. The author again describes how this new media “desacralized” the state (p. 182):

“NTV seized on Chechnya several months before the war actually started in December 1994. . . . The beginning of the war in Chechnya coincided with the launch of NTV’s satirical show Kukly (Puppets). Based on Britain’s Spitting Image, it featured rubber latex puppets of all of Russia’s top politicians and was unabashedly irreverent. . . . Russia had a long tradition of political satire but not of turning its leaders into funny puppets. The Kremlin rulers could be hated or loved, feared or despised, but they had always preserved some mystique that NTV deliberately sought to destroy, desacralizing state power at a time when the state was trying to justify its brutal war in Chechnya.”

In 1996, face with the prospect of a Communist victory in the elections, Yeltsin entered into a deal with the emerging “oligarchs,” essentially the top of the business class who used their wealth to buy political power. The author writes (p. 193):

“Business tycoons had a strong incentive for bringing Yeltsin to victory. A few months earlier Chubais had endorsed an audacious scheme devised by one of the oligarchs, Vladimir Potanin, to transfer control over Russia’s natural resources to a select group of tycoons in exchange for their political support. Known as the loans-for-shares privatization, it was the worst example of an insider deal and outright sham that the world had ever seen, and it has haunted Russian capitalism ever since. According to this scheme, tycoons would lend money to the cash-strapped government, and in exchange they would be allowed to manage the state’s shares. The loans would run out in the autumn of 1996—after the election. At that point, in theory, the government could repay the oligarchs, get the shares back and sell them in an open auction. But this was just a smokescreen for a quiet transfer of shares to hand-picked oligarchs. In practice, the government had neither the money nor the intention to buy back the shares. Foreigners would be excluded, and the oligarchs’ banks, which managed the shares, would auction them back to themselves.

Not only were the auctions fixed, but the money with which the tycoons had bought the state’s most lucrative assets had come from the state itself. The state, or its agency, would deposit money in one of the tycoons’ banks, which would then be used to bid for a company, while its workers’ wages and payments to suppliers would be delayed for months. The deal was a political pact between the oligarchs and Yeltsin since the second part of the deal—the actual exhange of loans for shares—depended on Yeltsin’s victory. “It was a small price to pay for averting a communist revanche,” Chubais said. In fact the loans-for-shares scehem was so unfair that it completely undermined its stated goal.

What is more, the deal was hardly necessary. The government did not owe any favors to tycoons. The risk of losing their wealth and influence—and their freedom—should Yeltsin be defeated was enough of an incentive.”

Yeltsin’s victory in the election with only 53.8 percent of the vote was not a result of “a broad coalition of democratic forces and parties but a narrow alliance of oligarchs and media managers. The actual democratic movement that had brought him to power in 1991 was virtually extinct.”

“Yeltsin’s victory was not a triumph for democratic institutions, the rule of law, and property rights. Rather, it was the triumph of those who had invested in and stood to benefit most from it—the tycoons and media chiefs. As Kirill Rogov, a political essayist and founder of one of the country’s first Internet news sites, noted, control over the media and its technology allowed the oligarchs to reach a goal that happened to coincide with the public good.

The 1996 elections and the loans-for-shares privatization turned business tycoons into oligarchs and journalists into spiritual leaders. Berezovsky boasted about it in an interview with the Financial Times. He spoke on behalf of the seven bankers who had participated in the Davos pact to have Yeltsin reelected. “We hired Chubais and invested huge sums of money to ensure Yeltsin’s election,” he said. “now we have the right to occupy government posts and enjoy the fruits of our victory.” With Yeltsin only semifunctional, the oligarchs felt they would be the ones ruling Russia.

“Berezovsky’s logic was very simple: if we are the richest, we must be the smartest,” said Chubais. “And if we are the smartest and the richest, then we should be ruling Russia.” They nominated Potanin, author of the loans-for-shares scheme, to be Russia’s deputy prime minister. Within a few months, Berezovsky was appointed deputy secretary of the Security Council. However, the main tool of power in the hands of the oligarchs was not their official jobs but their control of the media and, in particular, television. Yeltsin’s election persuaded the oligarchs that control over the airwaves equaled political power.”

Some of the liberals seems to have beliefs that strangely mirror those of the elite in the United States at the time, in terms of victory over past forces being final.

“In recognition of Malashenko’s role in the election campaign, Yeltsin asked him to be his chief of staff, one of the most important posts in the Kremlin. But Malashenko did something that was unprecedented: he turned Yeltsin down—a decision he would regret for the rest of his life. He did not do it out of false modesty or even humility. On the contrary, he believed that being in charge of a private television channel was far more important than being in charge of one of the Kremlin’s towers, as Yeltsin’s election campaign had just proved.

Having defeated the Communists and demolished the party of war in the Kremlin, Malashenko and Gusinsky felt invincible. The victory of liberalism in Russia seemed complete and final. “I did not see a political task,” Malashenko told me years later. “Now I understand that the central question in Russian political history is one of succession. If, back in 1996, I had realized that Yeltsin’s succession would determine Russia’s future direction, perhaps I would have acted differently. But at the time this did not occur to me.”

Malashenko was not politically ignorant, however, and had some idea of what he was doing (p. 203):

“For all the brashness and questionable origins of their wealth, he saw the oligarchs generally, and Gusinsky in particular, as private businessmen who’s individualism and initiative could keep state power in check. An extreme individualist and misanthrope, Malashenko had a low opinion of the masses. Liberalism and democracy were not synonyms to him but antonyms. Fascinated by Spanish history, he full subscribed o the ideas of Ortego y Gaset, who argued that democracy is no guarantee of liberalism and of individual rights and that any state, democratic or despotic, will seek to extend its powers and therefore needs to be countered with alternative sources of power that can be mustered only by private barons.

In the corner of Malashenko’s office at NTV stood a suite of genuine Toledo armor. His motto, displayed on his computer screensaver, was a quote from Ortega: “These towers were erected to protect the individual from the state. Gentlemen, long live freedom!” The tower in his instance was a television tower.

After seventy years of Soviet socialism, feudalism seemed like a step forward. The oligarchs were to his mind a lesser evil than those who had sacrificed millions of lives in the name of a strong state. With their taste for castles and private armies they seemed a good fit for the role of feudal barons.

But Malashenko had miscalculated. His idea that the oligarchs would defend private liberties and counter the power of the state was soon disproven as the oligarchs next brought a KGB statist to the presidential post. Their lack of historical perspective and above all responsibility meant that they used their money and power not to install rules and build institutions but to enlarge their fiefdoms and fight wats with one another and with the state.”

The author, of course, is referencing Vladimir Putin, who is soon to enter the story properly. At this point, it is worth reflecting on post-Soviet Russian history. The story the author has told us so far is one of a country who has no history and must not re-invent itself, but invent itself from whole cloth, as the title suggests. While a country called “Russia” existed before the Soviet Union, that country was far in the past. One must imagine one’s own country having no history whatsoever from the years 1917-1990, and then suddenly breaking free of the nightmare and having to make sense of what the country even was. The invention of Russia is somewhat like the invention of the United States. There was tumultuous period of revolution. Then the country emerged, but it was unclear exactly what had emerged. America was born out of England, but it wasn’t England. Russia in 1991 was born out of the old Russia, but it wasn’t that Russia, and it wasn’t the Soviet Union. The American Constitution wasn’t ratified until five years after the end of the revolution, and the Bill of Rights not until a year after that.

Postmodern Russia is still inventing itself. It is easy for westerners to view Russia as an anachronism, but it has yet to even fully develop a vision of what it is. The American government made a huge mistake in going to war with Russia in Ukraine, as it has provided a negative backdrop with which Russians can define themselves against. Difference is the key to nations. The West accuses President Putin of stirring Russian resentment of the West, but everything Putin has done, true or false, to create a Russian nationalism, has been done in partnership with the West.