Leaping Into The Future: China and Russia in the New World Tech-Economic Paradigm

Books Notes #32

Leaping Into The Future is the latest book from Russian Sergei Glazyev, Russian politician and economist, whose books The Last World War I had previously reviewed in this series. That title was a few years old; this new book will provide us with the freshest possible perspective from leading Russian geopoliticians and economic planners. It’s worth noting that this book was translated not into English by the Russians, but by the Chinese—Zhang Yumei, authorized by China Social Sciences Press. Strangely, the footnotes are left in Cyrillic.

My plan, as usual, is not necessarily to summarize the core thesis of the book, but find ideas of interest upon which to provide further commentary. The core thesis of the book, as expressed in the introduction, is as follows:

“The book presents the author’s Theory of Long Cycles in economic growth, which considers the fundamental significance of scientific and technological progress, the cyclical process of constant technological and world economic paradigm change, and the ensuing long fluctuation cycles and long cycles of capital accumulation. The theory reveals the objective reasons for the deep crisis and prolonged depression of the world economy, the outbreak of world wars, and social revolutions during the period of technological paradigm change. The world wars and social revolutions indirectly manifest the world economic paradigm shift. This theory enables us to explain the causes of the current world economic crisis and the expanding aggressive behavior of the US, whose ruling elite has launched a global hybrid war against China and Russia to preserve its global hegemony.”

One very interesting admission in the introduction is:

“Currently, the US has already been organizing a hybrid world war to maintain its control over its peripheral countries. But the main result of this war is the strategic alliance between Russia and China and the consolidation of China’s position as the leader of the New World economic and technological paradigm. Will this alliance be able to withstand US aggression and prevent a new world war? This book is written in detail about the strategy of the Russian-Chinese strategic alliance.”

In The Last World War, Glazyev expressed concerns that war with American and the outbreak of war in the Ukraine in particular would prevent Russia from becoming the leader of the new world economic paradigm if not adequately prepared, making it the junior partner to China. It seems that this text is making the admission that that outcome has occurred.

As far as why this book was written, the author explains his purpose as such:

“This book shows from a scientific point of view that the macroeconomic policy pursued by Russia is outdated, wrong, and harmful. The danger of market fundamentalist ideology for Russia and other countries on the periphery of the financial and economic system centered on the US lies in a lack of understanding of the laws of technological and economic development, which precludes a proper policy of modernization and raising the economy to the level of advanced countries. If Russia “slumbers” in the next technological revolution based on nano- and bio-engineering technologies, it will repeat the failure of the Soviet Union to take advantage of the achievements of information and communication technologies of the previous revolution, which will lead to political risks, serious technological lag, and poverty of working people. To eliminate such risks, the book offers scientifically sound recommendations based on the basic laws of economic development and the successful experience of China.”

Glazyev’s economic theories are explained in detail in the first part of the book, “Basic Laws of Economic Development.” In short, he believes in a scientific model based on a cyclic theory of Kondartieff (Nikolai Kondratieff) “Long Waves”, wherein technological paradigms emerge and decline, effecting an economic paradigm in their wake. The degree to which a country is aligned with emerging and presently mature economic paradigms will determine its future and present leadership in the world economic paradigm.

(p. 4):

“According to the author’s definition, the technology paradigm is a technology-related industrial cluster separated from the economic structure. These industrial clusters are connected through the same type of technology “chain” and form a reproduction whole. Each paradigm has an internally consistent and stable composition, which carries out a complete macro production cycle within the framework of the paradigm, including the extraction and acquisition of initial resources, all processing stages, and a series of final products that meet the corresponding public consumption types.”

Industries can be bottlenecked based on the degree to which they have or have not implemented the “foundation” innovations that allow for supplemental technologies that form technology chains in industry. It is for this reason that the mixed market and government controlled economy is necessary. The state must direct industry toward the next foundation technologies of the new economic paradigm, allowing for market innovations in creating it and supplementary discoveries, as well as the interconnections between the industrial “clusters” formed by these connected chains.

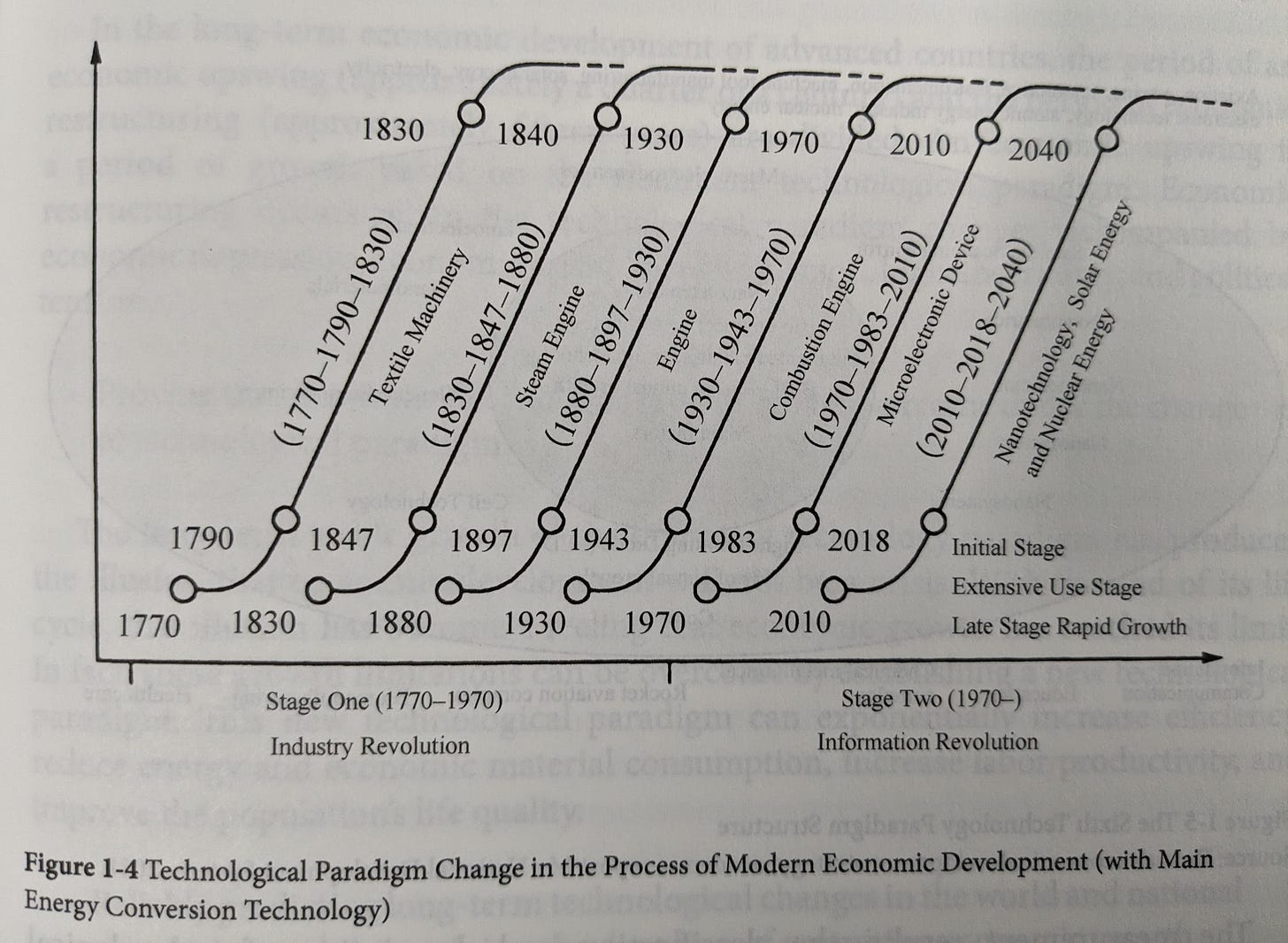

Here we can see charts that demonstrate the world economic paradigms as they exist:

In addition to technology paradigms, there are also world economic paradigms. It is important to comprehend that the terms “technology paradigm” and “world economic paradigm” represent two different but related concepts. Here, we can see the world economic paradigms charted with the corresponding technological paradigms and other cyclic patterns:

The author presents the history of these paradigms, which I have already summarized to some extent in the review of The Last World War.

In the imperialist world economic paradigm, the creation of credit currency (fiat) was the most important institutionalist innovation, giving the leaders of the paradigm long-term competitive advantages through seigniorage. For the industrial revolution to take place, according to Glazyev, credit expansion was necessary through the replacement of metal currency with paper currency, in order to facilitate the capital accumulation and international transactions.

(p. 35):

“Of course, the issuance of credit resources alone is not enough to promote economic growth. There is also a need for a system to ensure that credit is transformed into the expansion of production and investment, a need for technology and manpower that can guarantee engineering technology and organizational needs, and a need for a responsibility mechanism for the effective use and repayment of credit resources.”

The author next details the Federal Reserve system and examines the advantages for a country that controls the production of currency.

The information and communication technology complex is the core of the fifth technological paradigm. There is continuity between the fifth and sixth paradigms, that being information technology. The difference is that the fifth paradigm is based in microelectronics, whereas the sixth is based on nanotechnology, building structures directly on the atomic or molecular level.

The author addresses problems brought on by the digital revolution. For Russia, the country experienced a sharp decline in high-tech jobs. With a need for vastly more highly skilled workers and engineers than before in the next technological paradigm, the number of “white collar” jobs needed will exceed those no longer needed in low-skilled jobs, meaning that the threat of a sharp rise in unemployment is greatly exaggerated.

(p. 61):

“Ironically, the digital revolution, which is unfolding in the wake of the collapse of the world’s socialist system, can bring a qualitative “leap” to the effectiveness of national economic planning systems and a huge competitive advantage over capitalist countries.”

The digital revolution has also introduced new laws of economics in which old laws such as marginal utility no longer work (p. 62):

“The digital revolution has destroyed the usual rules of business. In the traditional sector, the more resources consumed, the higher the product price, but in the digital economy, the opposite is true: the more data you accumulate, the lower the cost of production. Neither the law of value nor marginal utility theory work in the digital economy. The accumulation of data can generate new data while reducing the cost of receiving other information. There is no material basis for the market valuation of Internet companies. As the scope of activities and market coverage expands, the marginal utility of investment increases rather than decreases as it does in the field of material production. The information revolution in the internet economy and finance makes the real sector a contributor.

The US-centric global economic paradigm is unraveling, and in the process, the digital revolution is creating more problems than opportunities for socioeconomic development. Even as the West “pulls” its economy with credit money, the lion’s share of its money issuance is still “absorbed” by the financial sector, while the productive investment sector stagnates. The institutional systems of the US, UK, and other capitalist countries are centered on the interests of the digital economy’s giants, rather than trying to mitigate the imbalances and eliminate the threats posed by the expansion of the digital economy. These problems hinder the productive use of new technologies and indicate that the existing world economic paradigm is not in line with the potential and needs of productivity development. This problem can be overcome by transitioning to a new world economic paradigm.”

Now, this claim about the destruction of the law of marginal utility in the digital revolution is suspect:

“Neither the law of value nor marginal utility theory work in the digital economy. The accumulation of data can generate new data while reducing the cost of receiving other information. There is no material basis for the market valuation of Internet companies.”

While there seems to be a high upper-limit to the amount of data that still proves valuable, it is, in fact, of marginally less utility at some point. For example, a machine learning model cannot effectively be trained with too small a data set. A large data set will produce a better model, and “big data” a very good model; however, the degree to which piling big data on big data increases the utility of the model will decrease as the excess data becomes superfluous to actual improvements to the algorithms. So it seems to be that there is such a thing as marginal utility in data.

Additionally, the claim that “there is no material basis for the market valuation of Internet companies” is patently false. Case-and-point: e-commerce. Some of the largest internet companies in the world are built on e-commerce, which is literally valued based on its facilitation of material transactions.

Unfortunately, a common pattern among Russian economists is the adoption of a “progressive” view of history, in which emerging technologies have somehow eradicated older laws of economics or otherwise made the impossible possible “because reasons”. I believe that, after the cataclysm of “shock therapy,” Russians have now become fascinated by the panacea of technology rather than of capitalism. It will no more be a silver bullet to cure Russian civilization of its ailments than capitalism was.

That is not to say that technology has not enabled “technique” that was previously thought impossible. But the Russians are not as divorced from America as they seem to believe. The management techniques they will use are fundamentally western. And the fact that their top economists are so glamorized by high technology points to misunderstanding of the uniform direction in which this leads.

The author comments on the shift in the status of countries as the new technology paradigm replaces the old (p. 64):

“In theory, the US can return to sustainable growth if the growth of the new technology paradigm is strong enough to generate income streams that offset the accumulated debt. However, the economic, financial, social, and technological development of the US is seriously unbalanced, and the institutional system that guarantees capital reproduction within the framework of the existing world economic paradigm is unlikely to return the US to a sustainable growth path.

The way out of the current slump will inevitably require massive geopolitical and economic changes. As before, “champion” countries cannot make fundamental institutional innovations, which can channel the funds released into restructuring the economic structure based on the new technological paradigm. The existing institutional system can continue to promote reproduction and truly serve the economic interests.

As mentioned above, the global economic structure is transitioning to a new technology paradigm based on nanotechnology, bioengineering, bioinformatics, information, and communication technologies. Soon, advanced countries will enter the “long wave” phase of their economic growth. The decline in oil prices marks the completion of the “birth” stage of the new technological paradigm. The rapid popularization of new technologies greatly improves resource utilization efficiency and reduces production energy consumption, making the new economic paradigm enter the stage of exponential growth. During a global technological paradigm shift, developing countries could make an economic “breakthrough” that brings them up to the level of developed countries, which are stuck investing too much in outdated production and technology complexes.”

On the philosophy of the new world economic paradigm, the author references the BRICS countries as an example of the basic principles of the paradigm at work (p. 65-67):

“Unlike the existing world economic paradigm, which focuses on the international financial and economic system as the basis for liberal globalization, the new world economic paradigm has a very diverse core. It is also reflected in the common values of BRICS countries, namely the free choice of development path, the denial of hegemony, and respect for the sovereignty of historical and cultural traditions. In other words, the BRICS represent a new model of cooperation that, as opposed to the unity of liberal globalization, respects diversity and is equally acceptable to countries at different stages of economic and social development.

Key elements of BRICS cooperation:

The shared desire of BRICS partners is to reform outdated international financial and economic systems that do not take into account the growing economic power of the emerging market and developing economies;

BRICS countries firmly support the unification of universally recognized principles and norms of international law and will not accept policies that impose military pressure and violate the sovereignty of other countries

BRICS countries all face similar challenges and issues, namely the need for a large-scale modernization of economic and social life;

Complementarity of BRICS economic sectors.

The historic mission of BRICS countries as a community of civilizations is to propose a new paradigm for meeting the needs of sustainable development, considering ecological, demographic, and social limits of development, and preventing economic conflicts. The BRICS shared principles of international organization are fundamentally different from the world economic paradigm shaped under Western European civilization, says Mr. Huntington: “The west won the world not through superiority of its ideas, values or religion, which few other civilizations converted to, but through superiority in organized violence. Westerners often forget this fact, but non-Westerners never forget it.”

The BRICS countries have established a new world economic paradigm based on equality, mutual benefit, and consensus. These principles have led to the creation of regional economic organizations such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, the EAEU, Mercosur, and the CHINA-ASEAN Free Trade Area, as well as financial institutions such as the BRICS Development Bank and the BRICS Foreign Exchange Reserve Pool. The new world economic paradigm is different from the liberal ideas of globalization today: The former is based on respect for the interests of the state, admitting to national limits on any foreign economic activities of the sovereign rights, following the principle of mutual benefit, and the principle of voluntary and international cooperation principle of common interests; while the latter only considers the interests of big capital dominated by US-centred multinationals. The free movement of capital, goods, services, and people should not be achieved by breaking down borders and destroying national institutions. Instead, the national interests of participating countries should be combined with institutional support for national development based on mutual and mutually beneficial investment. This will be the guiding principle for forming a new system of world economic relations. To use the terminology of John Perkins, the new system of world economic relations was built not by economic killers but by experts who planned complex webs of creative cooperation. Economic killers represent the benefits of large multinational capital colonizing peripheral countries. These experts, on the other hand, combine national competitive advantages to achieve synergies when implementing joint investment projects. Thus, using Sorokin’s definition, we call this new world economic structure an “integrated system.”

China is a model for Russia in choosing its economic development strategy. China is the largest neighbor and leader in establishing the new world economic paradigm and creatively applying the experience shared by China and Russia in building socialism.”

The final sentence leads us into the next chapter, on China being the center of the new world economic paradigm. Once again, the author admits the it will be China and not Russia that will lead this new paradigm. However, defeating the U.S. in its “hybrid war” to maintain its hegemony will require Eurasian cooperation between Russia and China (p. 72):

“Unlike the post-Soviet Union, China’s market economy advocates pragmatism and innovative reforms. The construction of the market economy in China is based on the practice of economic management rather than ideological dogmatism, which is disconnected from the actual process of social economy. Just as engineers design new machines, China’s leaders constantly improve new relations of production by solving specific problems, experimenting, and sifting for better solutions. China's leaders have worked patiently, step by step, to build their own socialist market economy, gradually perfecting the state’s management system and selecting institutions dedicated to economic growth and social welfare. While maintaining the achievements of socialism, the CPC has incorporated the regulation of market relations into the state management system and added the private and collective economy to the country’s basic economic system, so as to improve economic performance and benefit the whole people.”

A key statement on page 74 is: “China should not be regarded as transitional but as the most advanced social and economic system in the 21st century, i.e., the integrated world economic paradigm.”

The society and culture is neither capitalism nor communism, but “integrated.” Curiously, “integralism” and other “integrated” forms of economic paradigms are also being suggested in the U.S., possibly lending credence to the belief that this is the next world economic paradigm. Socialism and capitalism have been synthesized without the drawbacks of either in this system. At least, this is the claim of Glazyev.

It is true that China has undergone remarkable developments in its economic system over the last several decades. Whether or not this is rightly labeled as an “economic miracle” is up to the economists, but citing the 18th National Congress of the CPC (p. 76):

“We must unswervingly follow the path of socialism with Chinese characteristics in order to complete the building of a moderately prosperous society in all respects, accelerate socialist modernization, and achieve the great renewal of the Chinese nation.”

The author responds:

“Efforts along this path have indeed yielded tremendous results. Not because of the market mechanism, but because it is guided by the socialist goal of improving public welfare. Many superficial observers compare China’s economy to Lenin’s New Economic policy of the Soviet Union. The Soviet state a century ago was rebalanced with the help of private enterprise. Then communists saw that policy as a temporary retreat from socialist construction. Today, the private economy has become a regular mechanism to achieve the goals of social and economic development within the framework of socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

The author observes what the Chinese have learned and what the Soviets failed to implement (p. 77):

“The collapse of Soviet socialism was that its institutional system was not flexible enough to guarantee timely resource redistribution, and it could not transfer resources from an outdated production technology system to a more effective new production technology system. The Soviet socialist system’s understanding of the digital revolution was to automate the production process through special technical planning, so the Soviet Union created masterpieces for mass production, such as rotor automation production lines. But the planned economy remained “at the same level as before,” serving the endless reproduction of the same technology. As a result, the national economy of the Soviet Union was only a mixed economy at the technical level. Outdated industrial technologies consumed too many resources, leaving the remaining resources insufficient to develop new technologies. The strict hierarchical management system rejected the new opportunities created by the digital revolution. It continued the work method adopted during the First Five-Year Plan period, which was to increase production continuously. Unfortunately, excellent gross output eventually masked the flaws in the centralized planning system, where the marginal effect of investment in basic production tends to be zero.

The CPC has drawn the correct conclusions from the collapse of the centralized socialist economic management system and applied them to the self-organization mechanism of the market economy. At the same time, the centralized management system is retained in major fields such as finance and infrastructure to create conditions for the economic growth of enterprises. This revitalizes the economy, freeing management resources from rigid planning processes, focusing on strategic management, and coordinating socioeconomic interests to ensure economic reproduction for various social groups. Unlike the Soviet Union, China has transformed its economic management system from a technological and institutional perspective, weeding out outdated industries, stopping the supply of resources to inefficient firms, and helping advanced firms master the latest technology.”

The author also correctly observes that although the “imperialist” is also not strictly an economic model of competition between countries, and it advantages the “core” over the “periphery”, which can be exploited by the “core” primarily because the “periphery” lacks the financial institutions of the fifth world economic paradigm.

(p. 84-85):

The global competition under the world economic paradigm of the modern imperialism model (corresponding to the fifth technological paradigm) is not a competition amoung countries, but one among transnational reproduction systems. On the one hand, each transnational reproduction system integrates the country’s national education system, capital accumulation, and scientific research institutions. On the other hand, it unifies the production and financial structure of enterprises operating within the global market. These closely-connected systems determine the development of the global economy. After the collapse of the world socialist system, under the framework of global liberalism, the accumulation of capital in the US reached a new height. The result was the formation of a modern world order. In the modern world order, international capital and multinational companies refinanced by the Federal Reserve play a decisive role and constitute the “core” of the modern world economic paradigm. Countries that have not entered the “core” constitute the “periphery” of the modern world economic paradigm, and at the same time, lose their internal integrity and opportunities for independent development. The economic relations between the “core” countries and the “peripheral” countries of the global economic system are characterized by unequal exchanges. In this case, countries on the “peripheries” of the global economic system are forced to rely on natural resource rents and labor remuneration, exporting raw materials and low-tech goods and paying for the rental of imported goods and services.

By controlling the “peripheral” countries, the “core” countries possess the most high-quality resources of the “peripheral” countries-outstanding talents, scientific and technological achievements, and ownership of the most valuable part of the national wealth. The “core” countries rely on their technological advantages to force the “peripheral” countries to accept more beneficial standards and consolidate their monopoly in the field of technology exchanges. The “core” countries concentrate their fiscal potential, impose conditions on the capital flow of the “peripheral” countries and force them to use the currencies of the “core” countries, including the establishment of foreign exchange reserves. By establishing control over the financial systems of the “peripheral” countries, they distribute income within the global economic system. The “peripheral” countries are deprived of their main internal resources for economic development, and thus lose the opportunity to implement sovereign economic policies and manage their own economic growth and become an economic belt for the “core” countries of the world economic paradigm to obtain international capital.

The author notes that the theories he applies are not “dogmatic,” which is a difference between the Soviet system and the Chinese system that is emphasized several times.