85 Days In Slavyansk

Book Notes #20

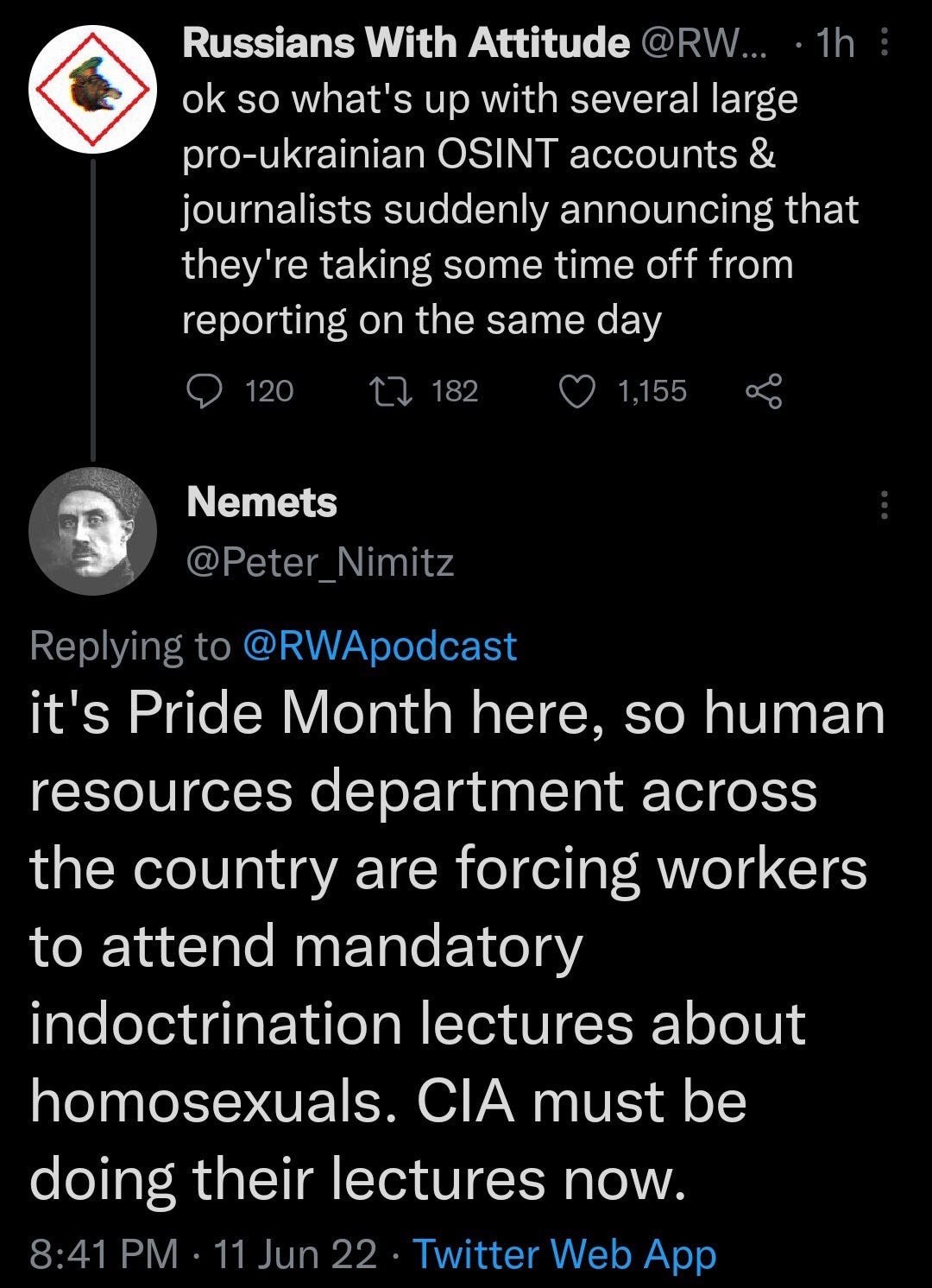

85 Days In Slavyansk written by Alexander Zhuchkovsky and translated by Peter Nimitz of Twitter fame: https://twitter.com/Peter_Nimitz

The author served in Slavyansk 2014 in Strelkov’s militia until they were encircled and broke out of the city. This book gives a history of the events leading up to the defense of Slavyansk, the defense itself, the authors participation of it, and the retreat and aftermath.

The book begins with a brief history of the 2014 uprisings against the Ukrainian regime in the “New Russia” regions of Ukraine, particularly the uprisings in Donetsk and Lugansk. I won’t recount those particulars here as that history lesson can be learned in other places, but of interest is this perspective on why the the 2014 war happened as was not resolved at the time.

“The rebels proclaimed the Donetsk and Lugansk People’s Republics after they occupied the major government buildings in Donetsk and Lugansk. They waited for the support of the Russian Federation, expecting instructions on annexation referendums. No instructions ever came. Instead Igor Strelkov arrived with the Crimean Company.

It is hard to imagine how events would have proceeded without Strelkov’s arrival in the Donbass. Perhaps the Russian spring in the Donbass would have ended in defeat as it had in Odessa, Mariupol, and Kharkov.

It should be noted that it is absurd to blame the events of 2014 solely on the USA or Ukrainian nationalists. They and others simply pursued their own particular interests which in this case conflicted with Russian interests. Much of the responsibility lies with the Russian Federation as it has pursued a weak foreign policy in the post-Soviet era. Russia supported Yanukovich twice in ten years while neglecting the Russians of Ukraine who wished to rejoin their motherland.”

As I have read more and more on the history of this conflict, I have come to the conclusion that the 2022 war is a result of weak Russian foreign policy on its doorstep. Since 2014, Ukrainian military spending increased dramatically in preparation to reconquer Donetsk and Lugansk.

As readers will know, the United States was backing the “color revolution” in Ukraine while the Russians were sitting on the sidelines, certainly not backing the Russian separatists in Ukraine as western media will proclaim.

“What happened in the Donbass in 2014 was entirely due to the Russian population of the region. Ukrainian propagandists claiming to see the hand of Moscow behind the uprising were wrong. It wasn’t until months after the start of the uprising that the Russian Federation began to intervene. Moscow did not initiate the revolution in the Donbass. It only reacted to it.”

While this is only the perspective of one soldier, it is theoretically corroborated by the fact that the outcome of the war was so dismal from the Russian perspective. The side with the superior organization won, and if Russia was so intertwined in these events as some claim, Russia ought to have easily had the upper hand, given its proximity not just geographically but also culturally, among many other reasons.

The beginning of the conflict makes for an excellent study in Elite Theory in action. Igor Strelkov organized a militia in Crimea that assisted with the Russian annexation. As no Russia assistance came to other parts of Ukraine, Strelkov organized an unofficial force of dedicated soldiers to come to the aid of Donbass. The author cites his conversation with one Sergey Tsyplakov, who facilitated critical communications between Strelkov and Donetsk.

“In March – April 2014, the pro-Russia movement was at a dead end. We failed to take over the region with non-violent protests, and there was not enough strength for an armed uprising. By non-violent protests, I mean, for example, work stoppages, mass street protests, etc to paralyze the economy of the region (25% of the economy of Ukraine). That would force the local elites to join with the protestors, similar to what occurred in Crimea. However, we had two problems. The first was that we didn’t have enough time and people to organize a large enough protest. The second was that there was simply no one to negotiate with. The Donetsk political elites are tightly knit and criminal, with many linked to violent gangs. To negotiate with them would leave one dead and buried in garbage.

At the same time, we were also incapable of armed resistance. Few people at the time were willing to kill or die for the cause. Ordinary working people are very law abiding. They are used to strictly following instructions in factories and mines, so better at taking than giving orders. While this makes for a good and peaceful society, it was necessary for independent and decisive action in spring 2014.”

“After unsuccessful attempts to seize administrative buildings and the capture of Pavel Gubarev, the protests began to slow down. Buildings were stormed and then abandoned. The protests had flared, but then dimmed. We needed to act more radically to capture the SBU, the Ministry of Interior Affairs, and the TV tower. We also wanted to take the airport, hoping that that would trigger the arrival of the Russian Army and ensure the safety of Donbass.

The local elites were waiting to see what would happen at that point. Some were waiting to see what the Russian Federation would do and demanded guarantees of their position or safety. Others took a pro-Ukrainian position, or remained neutral. We realized that it was necessary to seize weapons and dictate terms to them ourselves. We saw what had happened in Crimea and hoped for Russian help as well.

The Kiev junta had already moved forces into the Donbass between 20 and 30 March. Key participants of the protests had been arrested, and repression had begun. In response, we continued organizing rallies.

We again occupied the regional state administration and the SBU buildings on 6-7 April. We were able to seize the weapons there, but there were few of them. The Ukrainians had already removed most of the weapons. We found 60 guns there, as well as more at the fort. Overall, we had no more than a hundred guns. It is impossible to organize an uprising with so few weapons. At the time, the People’s Militia of Donbass was compromised of only a few hundred people and lacked both discipline and leadership. They were all just waiting in their apartments to be arrested.

We had committed serious criminal offenses, and by doing so everyone was committed to going forward to the end. If we didn’t, the consequences would be dire. We saw how the protests had ended in Odessa and Kharkov. As we prepared for the worst, Igor Strelkov and his men arrived, the Battle of Slavyansk began, and the militia escaped defeat.”

The arrival of Strelkov’s fifty-two men provided the necessary organization. They were described by a militiaman as such:

“Do you know how Strelkov’s men differed from the locals? They smelled like war and exuded some unfathomable sense of determination. They arrived understanding that they would fight and shed blood. They were ready for anything.”

The author provides a decent biography of Strelkov, both in his strengths and failings. The end of that chapter will suffice as a good summary of what Strelkov saw himself doing in his defense of Slavyansk:

“The enemy’s goal in this long-prepared “revolution” is chaos in Ukraine and on the Russian frontier. For them, the bloodier and more destructive the chaos, the better. Unfortunately, many Russians fail to understand that there is no avoiding this chaos except through firm and decisive military action. Too many try to resolve these festering issues with homeopathic cures when only an urgent surgery can remove these tumors from an increasingly unhealthy body. Our mission is to give Moscow time to understand this and to agree to an operation.”

Clearly, Moscow eventually decided on the “Special Military Operation,” but far, far later than Strelkov and others would have liked. Russia is now paying in blood and treasure for its indecisiveness.

The author offers three possible theories for the actions of “former” FSB officer Strelkov:

“First possibility: At the beginning ofApril 2014, Russian authorities planned to send troops to Ukraine and implement the Crimean scenario, at least in Donetsk and Lugansk. Similar to Crimea, they sent a small armed group of special forces to prepare for the arrival of regular troops.

Second possibility: Russian leadership did not have any firm intentions and plans for Ukraine, therefore it could not give an order or a green light to Strelkov and his men for military action. However, patriotic elements of the Russian elites were interested in aggressive actions towards Ukraine. Those elites include the famous Orthodox oligarch Konstantin Malofeyev, the head of Crimea Sergey Aksyonov, and the political strategist Alexander Boroday. Recognizing that the Kremlin was hesitant but not opposed to aggressive actions, these elites took the initiative themselves and authorized Strelkov to intervene in the Donbass.

Third possibility: The decision to intervene in the Donbass was made entirely by Strelkov and his men. They went to Donbass without and orders or support from above, just as hundreds of Russians would over the next few months.”

The author sees serious flaws in all of these theories. It seems like the events surrounding Strelkov and Slavyansk could not have happened without Russian support, and yet there was no follow-through as in Crimea; it likewise seems impossible that he acted on his own. The author describes power in Russian politics as “distributed vertically,” leaving no room for independent parallel action, yet ends up regarding the second theory as most likely. Strelkov himself told the author that he was in agreement with Prime Minister Sergey Aksyonov in his decisions, and it is an open secret that Malofeyev financed Strelkov and the Donbass militias. There is also evidence that other parties in Moscow tried to counteract this support and divert Strelkov from his objective, so it appears that the Kremlin did not have a strong plan for what to do in Donbass.